Rating: ExcellentMany years ago I became a casual fan of the Bee Gees, specifically their 1969 album Odessa, a double album that is eccentric, over the top, fascinating and, as I concluded after a while, pure genius. Over the years I've bought quite a number of their albums second hand and have become a big appreciator of the Bee Gees unique musical world. Their albums are still cheap to buy, despite second-hand vinyl prices rising in general due to the demand generated by a new generation of collectors and vinyl lovers, because, well, the Bee Gees are still pretty uncool. They may be uncool, but the reality is that they were song-writing geniuses. Children of the World delves deeply into both the Bee Gees personal lives and their music, with the emphasis on their music. Somehow Bob Stanley has managed to give the reader a well rounded sense of the Bee Gees as people, whilst mostly being concerned about their music. Stanley notes that the three Gibb brothers, Maurice, Robin and Barry, were basically outsiders, despite their stellar commercial successes. They lived in their own hermetically sealed world, for example, he points out, that even their version of disco was very different to that of other acts disco; in one of Stanley's many great lines, he compares Bee Gees disco to a wafting summer night's breeze, as opposed other acts disco, which he describes as like stepping into the oversaturated perfume section of a department store. In telling the Bee Gees musical story, from the Isle of Mann, through to their decades of both slumps and global dominance, Stanley writes supremely well about music. To convey both the technical aspects of music and its intangible magic, is a very difficult thing to do without resorting to cliches, but Stanley manages it. Essentially Children of the World is perhaps the best music book I've ever had the pleasure of reading.

|

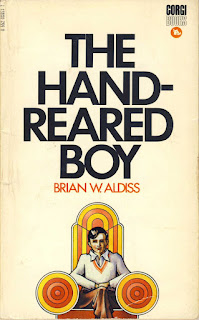

| Odessa - eccentric brilliance |

One of the things that Stanley does best is make you want to hear the music he's talking about, so be prepared to be listening to the Bee Gees a great deal whilst reading. It is double the pleasure basically. Stanley also begins each chapter with a rundown of either the US top ten chart, or the UK top ten chart, which gives the reader great context regarding the musical world the Bee Gee's were existing within. The thing that Stanley convey's really well is just how unique the Bee Gee's were, there is nothing else like them in the history of popular music really. It is best to read this book, as it is difficult to explain this adequately within a few words, however, to give it a go, the Bee Gees were kind of kooky, eccentric and unhindered by the kind of restraint that rendered many other commercial acts of their era banal. Actually to understand the Bee Gees unique appeal it is best to start listening to them properly, not just their many hits; albums like Idea(1968), Odessa (1969), Cucumber Castle (1970), To Whom it May Concern (1972), Trafalgar (1971) and Main Course (1975) would be good starts. The story of the Bee Gees is one of true graft, they worked really hard, sheer musical talent and also personal and family troubles and tragedies (no pun intended). Andy Gibb's story is also included, which is both inspiring and very sad. Like Brain Wilson, Barry Gibb has ended up being the last brother left in the family, with the premature deaths of Maurice and Robin. Stanley has been criticised for paying scant attention to their deaths in the book, but he deals with their deaths with taste, and besides, it's mostly all about their lives and their music. Another criticism is that there are no photos included, however this is barely noticed, as Stanley's writing is so good images are rendered unnecessary, besides, that's what the internet is for. Essentially Children of the World is a must for Bee Gees fans, and if you are a casual admirer of their music, reading the book will turn you into a big fan, which is one of the best things that could happen to you frankly, just make sure you don't care about being cool.

|

| The Bee Gees in action, circa the late 1960's |